One of Trump’s consistent economic talking points (read: recurring tweet topics) has been laying into Jerome Powell and the Federal Reserve for raising interest rates:

Objectively, these tweets make little sense. Still, all politics aside, I think the underlying question “should the Fed be doing what it is doing in this macroeconomic environment” is always a fascinating thought experiment. I have been quite hawkish in the past, but recently I have encountered compelling arguments to keep rates low and take a more dovish stance. For that reason, I’d like to unpack the following:

What interest rates are we talking about exactly, and what has the Fed been doing with these interest rates (during Trump’s presidency)?

What constitutes the current case for raising interest rates?

What constitutes the current case for cutting interest rates?

What do I think?

As a disclaimer, this is a simplification of the theses in key debates surrounding the Fed’s interest rate decisions today. Monetary policy is at the complex and confusing intersection of the empirical and the theoretical such that there is always one more layer of nuance to be explored. With that being said, let’s dig in.

1. Fed Interest Rates

A. What are the “interest rates” everyone keeps talking about?

For some background, the system of monetary policy that the Fed has used since the financial crisis is quite complex. In short, the Fed works with a few interest rates, the most important of which are:

The Federal Funds Rate - the interest rate which banks charge one another for one-day i.e. overnight lending. The Fed has a target range for this rate and uses monetary policy (adding or withdrawing money from the money supply, etc.) to affect this rate

Interest on Reserves and Interest on Excess Reserves (IOER) -

Financial institutions are required to hold reserves with the Fed as a buffer for their stability. They also effectively serve as checking accounts for these banks if they need to make large payments

There are two separate interest rates that the Fed banks pay to these institutions. One on the reserves at or below the requirement and one on reserves above the requirement (i.e. extra buffer)

Interest Rate on Primary Credit (a.k.a the discount rate) - the interest rate at which the Fed lends to commercial banks in its role as a lender of last resort

Overnight Reverse Repurchase Agreements (ON-RRP) - the interest rate at which financial institutions lend to the Fed, just like reserves held at the Fed, but the difference in this case is that the Fed puts up securities as collateral

The Fed moves these rates together to create a target range in what is called a floor-with-subfloor system. This system is explained well here by Brookings but the short idea is as follows. The Fed Funds Rate is the primary tool of influence by the fed, and the Fed Funds Rate should (in theory) lie between the IOER and the ON-RRP (above ON-RRP and below IOER). This is because a bank lending money would generally want more interest than that provided by ON-RRP (the collateral securities reduce risk) and market efficiency would not allow the Fed Funds Rate to be higher than the IOER as banks would move excess reserves to the Fed funds market if that were the case, eventually pushing the Fed Funds Rate back down. (There are rumblings that this system is not sustainable in the medium to long-term, but I won’t dig into that here).

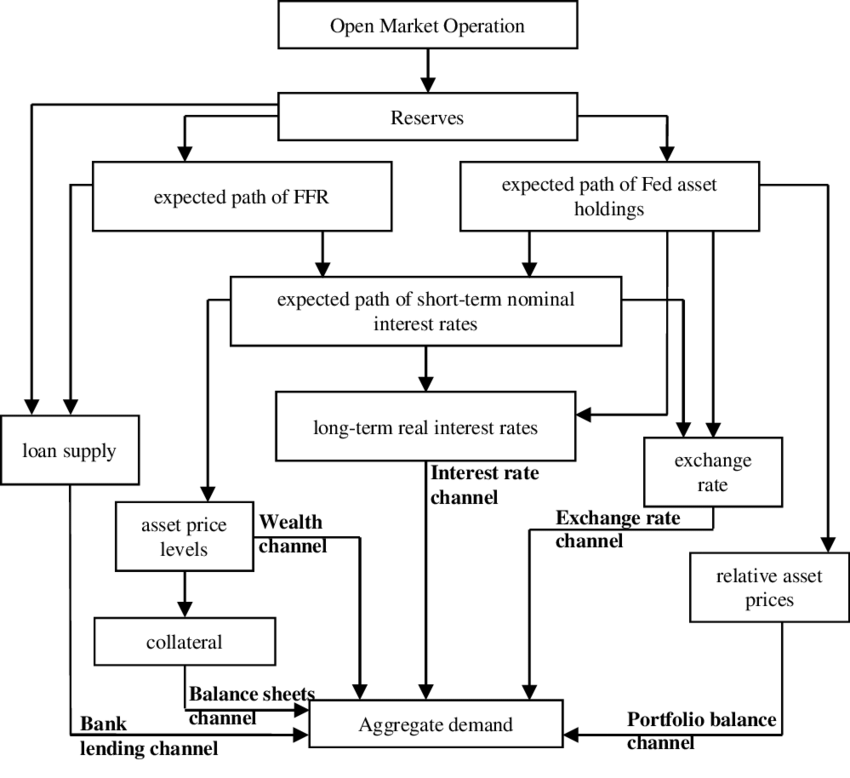

All of this seems fairly abstract, but these interest rates flow through the entire economy and affect all businesses, households, and individuals. There are numerous direct and indirect channels of monetary policy transmission explained well by this publication by the Boston Fed and the graphic below:

B. Balance sheet reductions

During the financial crisis, one action the Fed took was to buy certain assets from financial institutions to create liquidity in paralyzed markets and keep these institutions from failing. At its peak, the size of the Fed’s balance sheet was a whopping ~$4.5 trillion. In October 2017, the Fed decided it was time to wind down the size of the balance sheet and began allowing Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities to roll off its balance sheet at a rate of $30 million and $20 million per month respectively. The end of this program is planned to be in September of this year. According to the Fed, this balance sheet reduction can increase the effective Fed funds spread by 0.5 basis points and the ON-RRP spread by 2.1 basis points for every $100 billion rolled-off the balance sheet causing a further creep upward in the Fed Funds Rate than what is expected by setting the floor and subfloor.

C. What has the Fed been doing?

Since Trump took office in January of 2017, the Fed has increased the target range for the Fed Funds Rate 7 times by a total of 1.75% from a target range of 0.50 - 0.75% in December 2016 to the current target range of 2.25 - 2.50%. Over this period the Fed has also consistently been allowing Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities to mature and roll off the Fed’s balance sheet, also pushing the effective Fed Funds Rate upward.

2. The Case to Raise

Overheating

Overheating is if an economy has experienced prolonged periods of high growth it may be at risk for spikes in inflation, instability, and asset bubbles

Tell-Tale signs of an economy overheating include increasing inflation rates (inflation is recovering but is still below the Fed’s 2% target) and decreasing unemployment rates (we have definitely seen this, though there are a lot of nuances here regarding participation and NAIRU)

The point? — if the Fed believes there is a risk of the economy overheating and causing an “economic burn-out”, raising rates should pull the reins on the economy a bit to keep things in check

Policy ammo

In the face of downturns, the Fed would theoretically like to lower rates to provide easy credit and stimulate economic growth, but it can’t do this if there are no interest rates to lower

In the last three recessions, the Fed cut interest rates by ~5%, current rates are sitting at about half that

The point? — if interest rates remain low and we arrive at another serious recession, the Fed will have very little “ammo” in the chamber to influence the economy. So, as silly as it sounds, the Fed may want to raise rates now just so it can lower them when the time comes later

Choose your own basket of economic indicators

Things get tricky when people begin to cite certain economic indicators (with different controls and over different periods) to tell a story for why the economy is overheating or on the cusp of doing so

Here are a few people are citing today in theses for why to raise rates:

Unemployment rate (U-3 and U-6) —> lower than usual and potential sign of overheating

Job growth (the number of jobs available) —> strong growth can indicate strength in the economy

Current GDP growth —> particularly topical as it is a Trump favorite — strong growth can indicate strength in the economy. This can be a bad metric for real-time policymaking as GDP growth is often revised such that we do not know the actual GDP growth numbers until months or even years later

Borrowing rates (30-year fixed mortgages, new car loans, variable-rate credit cards) —> borrowing costs rising, a good trend to maintain by raising rates to avoid overheating

Real (inflation-adjusted) interest rates and r* (the neutral and equilibrium level for the real interest rate) —> argument to be made depending on one’s belief in and adherence to the Taylor Rule

3. The Case to Cut

Inflation and the Phillips Curve

The Phillips Curve has historically described the relationship between unemployment and inflation (they move in an inverse relationship)

Recently, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell said that relationship was gone, which we can see in that inflation has grown modestly at best since the financial crisis while unemployment has dropped to around 3.8% since the recession

The Fed has a dual mandate to maintain unemployment and inflation targets, and while unemployment has indeed fallen below that target, the economy has yet to muster up an inflation rate consistently at the Fed’s target rate of 2%

The point? — if the Fed has not conceded to there being a “new normal” (i.e. inflation no longer moves with unemployment as it used to) and the Fed believes it must pull up inflation to its target of 2% to bring “normalcy” back to the economy, it may decide to cut rates to loosen the reins a bit on inflation and allow the economy to run hotter

Sentiment on systemic and global risk

There is some concern at the Fed about increasing systemic risk and uncertainty that the Fed should account for in its policy, some examples of this:

US-China trade war

US fiscal budget crises

Weakening economic growth globally

Brexit risks

The point? — exogenous factors can have very real impacts on the US economy that the Fed needs to factor into its assessment of economic health and if the Fed sees signs of serious incoming pressure on the US economy it may want to cut rates to bolster the economy in the face of those pressures

Choose your own basket of economic indicators

As above, things get tricky when people begin to cite certain economic indicators (with different controls and over different periods) to tell a story for why the economy needs a rate cut

Here are a few examples people are citing today in theses for why to cut rates:

Inflation rate (CPI or PCEPI) —> too low and potentially suppressed by increasing interest rates

GDP growth changes over time —> slowing growth or signs of slowing growth can indicate weakness in the economy

Job growth (private sector employment) —> slowing growth or signs of slowing growth can indicate weakness in the economy

Wages and measures of slack —> not responding the way one would think to the low unemployment numbers indicating the economy is not running hot and there is more slack (unemployed or non-utilized resources) in the economy than it may superficially appear

4. What Do I Think?

While there are compelling arguments to be made to raise or cut rates, I believe holding rates would be wise for now (much like the Fed has been since the start of 2019). At a high level, the fact that there are enough indicators to create a compelling case to cut rates is enough evidence that one should be wary of rate hikes. Combine that with the fact that more nuanced measures of slack in the economy and current inflation rates do not indicate any sort of overheating and suddenly all potential urgency for a rate hike is subtracted from the equation.

On the flip side, things simply do not look bad enough for a rate cut. Cutting rates before actually entering a recession would not be prudent monetary policy, especially with rates as low as they are now. Cutting rates now could extend the current upswing but would do little to mitigate the risk of an upcoming recession and would give the Fed less ammo for when the music really does stop. Despite how ominous the current list of global economic risks may sound, cutting rates to give the economy a bit of a nudge in the face of these pressures seems short-sighted.

Moreover, none of the global risk factors recently cited by the Fed are new. Most of these systemic risks, including Trump’s trade war, have been ongoing for months now. This begs the question, why cut rates this month on essentially the same information you had last month? Doing so would effectively pull the curtain on the Fed revealing a policymaking process that is not nearly as objective or data-driven as the public would hope.

Addendum: I wrote this post before the Fed announced to cut rates by 0.25% at the end of July and to end the balance sheet reduction program early, with the size of the balance sheet still nowhere near pre-crisis levels. As mentioned above, I don’t necessarily agree with that policy decision, but as is also mentioned above, there is a case to be made that it was the right decision. Only time will tell. The Fed’s signaling as to why it was cutting rates at this meeting of the FOMC was centered on global risk, market sentiment, and Powell potentially implied it was a “re-calibration” as discussed in the Upshot here. Again, cutting rates without a current or imminent looming recession is fairly unconventional, but in this case, it may be an attempt to give the economy some room to run so the onset of the next recession is not too severe. Also, The Daily did a great ~25-minute episode on August 1st that includes a simple intro to the Fed and the current state of affairs for monetary policy in the US.

Key sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14

*Disclaimer: this is an opinion piece that is derivative of outside research and public sources. This is not investment advice and should not be interpreted as investment advice. This article does not in any way reflect or represent the view of my employer, colleagues, friends, or family.*